5.1 Overview

1

The New Zealand Security Intelligence Service is New Zealand’s human intelligence agency.

2

In this chapter we:

- describe what human intelligence brings to the counter-terrorism effort;

- discuss the roles of the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service;

- explain its leads process;

- discuss the rebuild of the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service; and

- assess the evolution of their counter-terrorism efforts.

5.2 What does human intelligence bring to the counter-terrorism effort?

3

Human intelligence can enrich intelligence obtained from other sources, by providing insights into the motivation and intention of individual actors, which may not be apparent from signals intelligence alone (see Part 8, chapter 7). Intentions and motivations will vary from one person to another and change over time. Understanding people and all their complexities is crucial to the collection of human intelligence.

4

A human intelligence agency offers the national security system and the counter-terrorism effort expertise in making sense of information from multiple sources with a view to developing a deeper understanding of the security environment.

5

Ideally a human intelligence agency’s all source analysis will generate a strong understanding of the threatscape. It is used to identify emerging threats, supports disruption and enforcement carried out by law enforcement agencies and informs decision-making elsewhere in government (for example, immigration decision-making).

5.3 Roles of the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service

6

The New Zealand Security Intelligence Service is a specialised human intelligence agency.75 Its objectives include the protection of New Zealand’s national security,76 including protection from terrorism and violent extremism.77 It operates by obtaining human intelligence from people with knowledge of, or access to, information. It also obtains information through a range of other collection methods. These include physical surveillance, open-source research and activities conducted under intelligence warrants, such as the use of tracking devices, telecommunications interception and listening devices.

7

The New Zealand Security Intelligence Service has a broader remit than its comparable international partner agencies. For example, in Australia there are separate agencies for managing domestic security threats (Australian Security Intelligence Organisation), foreign intelligence (Australian Secret Intelligence Service) and vetting (Australian Government Security Vetting Agency). All of these activities are undertaken by the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service. This broad range of functions impacts on its decision-making, including its prioritisation and resourcing decisions.

5.4 Leads process

8

A security intelligence investigation always starts with information, which is assessed for its relevance to national security by an investigator.

What is a lead?

9

Lead information can take many forms, such as a name, a phone number or an activity of security concern. A lead is formally raised if the information and intelligence is both relevant to New Zealand and shows a possible threat to national security (such as terrorism or foreign interference).

10

Information or intelligence that does not meet these two criteria is not raised as a lead or investigated further by the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service. It may, however, be referred to another domestic agency (such as New Zealand Police), particularly where the information suggests criminal activity is taking place.

Where does lead information come from?

11

Lead information comes from a wide range of sources, including:

- other New Zealand Security Intelligence Service investigations or business units;

- international partners;

- other Public sector agencies (such as New Zealand Police or Immigration New Zealand); and

- the New Zealand public.

12

Lead information received (or generated) by the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service that relates to terrorism is dealt with and managed by the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service’s Counter-Terrorism Unit. During 2017-2018, the Counter-Terrorism Unit received about 150 terrorism-related leads. Most of these leads related to individuals allegedly viewing violent terrorist propaganda, supporting or seeking to support the activities of Dā’ish or attempting to travel from New Zealand to join extremist groups or terrorist entities.

Progressing lead information to a lead and then to an investigation

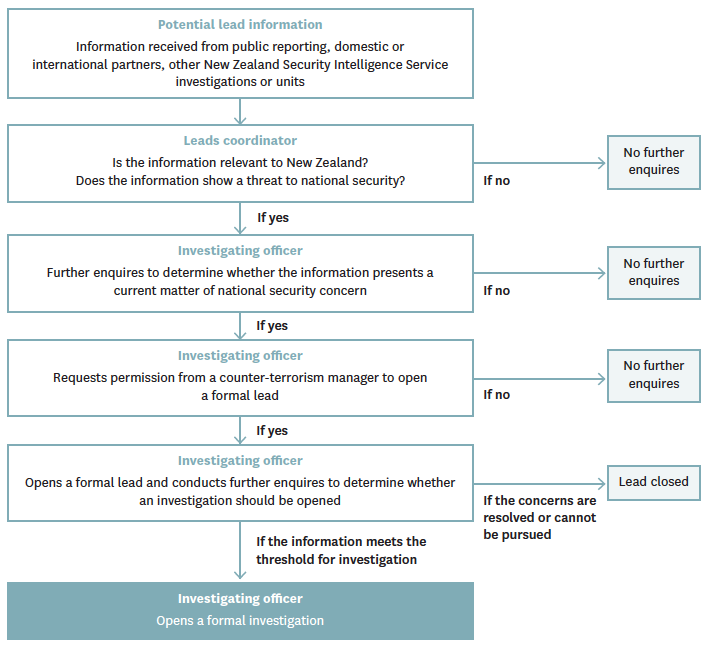

13

Lead information is initially dealt with by a leads coordinator, who is responsible for making a preliminary assessment. The leads coordinator determines whether the information is relevant to New Zealand and shows a possible threat to national security.

14

The leads coordinator is responsible for allocating the lead information to an investigating officer. The leads coordinator is not formally responsible for progressing the lead information once it has been allocated to an investigator. The investigator is responsible for evaluating the lead information and recommending whether a formal lead should be opened based on whether it presents a current matter of national security concern. This will be approved or declined by a counter-terrorism manager. A counter-terrorism manager will maintain oversight of the lead process and provide guidance where necessary.

15

Investigating officers must capture all leads in what is known as the Leads Workflow Tool. This tool provides for the active management of leads, ensuring that decisions are documented and that actions taken against each lead are accurately recorded and tracked.

16

The Leads Workflow Tool requires investigating officers to assign a priority to the lead. The New Zealand Security Intelligence Service prioritises leads according to whether they are high, medium or low priority:

- High/critical – time sensitive and requires immediate action (for example, involves a threat to life).

- Medium – time sensitive, has an accountable deadline and must be actioned in a timely manner.

- Low/routine – not time sensitive and must be worked on when the investigator has capacity or cannot be looked at due to limited resources.

17

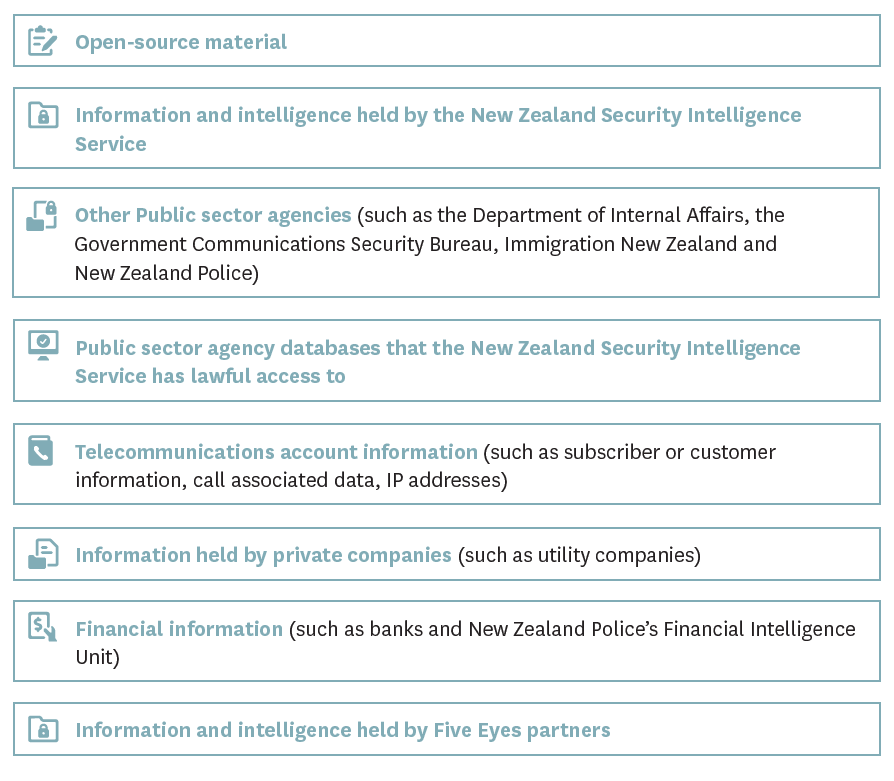

Once a priority is assigned, the lead is actioned in the Leads Workflow Tool by the assigned investigator. The investigating officer will identify the intelligence gaps that exist in relation to the lead and seek to address those by carrying out various inquiries. These involve checking one or more of the sources outlined in the figure below.

Figure 44: Information and intelligence that may be checked during a lead assessment

18

Through these enquires the investigating officer seeks to understand more about the lead information, such as the nature of the links to national security, the credibility of the information and the urgency it presents. Depending on what information comes to light, the lead may be progressed to an investigation.

19

Although the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service has guidelines for the commencement of an investigation, there are no hard and fast rules for deciding if a lead should move to a full investigation. Instead, it requires the judgement of the investigator (and their manager) to the particular facts relating to the lead. Depending on the nature of the lead, some factors (such as the imminence of harm) may outweigh other factors (such as the reliability of the lead). Given each lead is unique, a definitive threshold is not applicable.

20

An investigation may extend to covert collection, which may require an intelligence warrant to undertake activities that would otherwise be unlawful.

21

The principles of proportionality and necessity will be relevant in determining what investigative activity to undertake (see Part 8, chapter 14). The principle of proportionality requires investigators to consider both the intrusiveness of the proposed action and the priority of the lead. Counter-terrorism managers are responsible for overseeing whether the proposed actions are necessary and proportionate.

22

If the investigator’s enquiries resolve national security concerns or cannot usefully be pursued, the lead is closed with an explanation of the reasons recorded in the Leads Workflow Tool. If the lead has been referred to another Public sector agency, such as New Zealand Police, this will be recorded.

Figure 45: Progressing lead information to a lead and then to an investigation

March 2019 developments

23

In August and September 2019, the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service conducted a review of its leads processes. It decided to adopt the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation’s leads triage and assessment framework. This provides a standardised set of criteria for the evaluation of information, including security and radicalisation indicators, and outlines the process for the assessment and management of leads (see Part 8, chapter 12).

24

The framework sets out three stages for assessing a lead:

- Evaluation and prioritisation (Stage 1) – incoming lead information is triaged and prioritised according to security indicators and urgency. Information gaps are identified and inquiries are made to fill the gaps.

- Development and assessment (Stage 2) – based on the information gathered, an assessment is made and inferences are drawn to determine the requirements for further enquiries.

- Action (Stage 3) – the lead is either elevated to become a formal investigation or closed.

25

At Stage 1, the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service applies the Reasoned Assessment Model to assist investigators in evaluating and prioritising incoming lead information. Under this model, incoming lead information is evaluated and prioritised by a preliminary assessment of:

- the threat posed by the lead information – this is measured by the intent (motivation, desire and confidence to carry out an attack), capability (knowledge and resources for conducting an attack, such as access to, and ability to use, weapons) and imminence of the threat;

- the relevance to national security;

- the plausibility, reliability and credibility of the threat and corroboration of the lead information (this includes assessing the source of the lead information, including the chain of acquisition and motivation of the source); and

- the connection between the lead information and New Zealand.

26

To assist staff in prioritising leads, the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service has produced a table that sets out various security indicators and the priority associated with them. For example, “Skills/Knowledge – Research into basic weapons, firearms and ammunition” is identified as a critical indicator of security relevance for assessing whether a person has the capability to carry out a terrorist act. The number of security indicators (and the priority associated with them) that a lead displays is relevant to its overall prioritisation. The New Zealand Security Intelligence Service guidance sets out that where a lead displays two or more security indicators, it can be prioritised as medium.

5.5 The rebuild of the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service

27

The New Zealand Security Intelligence Service’s capability and capacity were severely degraded by 2013–2014.78 As at 30 June 2014, it had 225 staff. Around 35 to 50 percent of these staff were allocated to security vetting and just 4.5 full-time equivalent staff (including the manager) worked on terrorism investigations. This was less than one staff member working on terrorism investigations per million people in New Zealand. The staff working on terrorism investigations were supported by intelligence collection and analytical staff.

28

By 2016 there had been an appreciable increase in the Counter-Terrorism Unit’s investigative staffing. But a large proportion of this was associated with a dedicated one-off investment by the government for a specific and narrow purpose.

Strategic Capability and Resourcing Review programme

29

From July 2016, the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service received increased funding associated with implementation of the Strategic Capability and Resourcing Review (see Part 8, chapter 2). This allowed significant growth over four years in its capacity and capability. The increased funding was approved with the condition that the New Zealand Intelligence Community would not seek additional funding until at least February 2019, unless there was a major security or global shock.

30

The anticipated capability increase was described in this way in a February 2016 Strategic Capability and Resourcing Review Cabinet paper:

The capability increases from a current state where partial monitoring of watch-list targets is possible and there is minimal coverage outside Auckland, to a future where there is a New Zealand-wide baseline threat picture … .

31

Since 2016, the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service has undergone rapid organisational growth and organisational and business renewal. It has engaged in the development and implementation of a fundamental redesign of its governing legislation (the Intelligence and Security Act 2017) and responded to enhanced and more rigorous oversight.

32

Growing capacity and capability in intelligence and security agencies is not straightforward. This was recognised by United Kingdom agencies in their response to questioning by the Parliamentary Intelligence and Security Committee inquiry into the 7 July 2005 London terrorist attacks. When asked whether agency heads ought to have sought a greater increase in funding in the previous year, the Chief of the British Secret Intelligence Service said:

If you try to bring in more than a certain number of new people every year, you can literally bust the system … you can only tolerate a certain number of inexperienced people dealing with sensitive subjects.79

33

During the initial phases of the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service rebuilding exercise the primary focus was on enabling functions (for example, security vetting and then compliance and organisational processes and systems) rather than frontline staff. By 2018, a significant number of new investigators and some new collection staff had been brought on board and, as of late 2019, numbers had recovered considerably from where they were several years ago. A consequence of this sequencing is that the numbers of the current investigators and a certain category of collection staff is proportionately low and many have limited experience. The 2019 Arotake Review confirmed this view, noting that the majority of the investigators had less than one year’s experience at the time of the 15 March 2019 terrorist attack.80

34

We were told that getting the balance between investigative and collection capabilities right is difficult, as a certain category of collection staff are particularly difficult to train and develop. While there is no set timeframe, as different people develop at different rates, collection staff were generally regarded as apprentices for at least their first year.

35

Capacity and capability gaps can have flow-on effects for other parts of the organisation. Investigations staff need experience to know how to effectively task collection staff. We heard that the limited experience of some investigations staff led to extremely valuable collection staff being deployed against lower priority intelligence requirements instead of developing more strategic access. The New Zealand Security Intelligence Service has sought to address this through the establishment of a Collection Hub, which facilitates interaction between investigators and collections staff. The Collection Hub ensures that intelligence requirements are refined and prioritised according to urgency and available collections resources.

36

We were also told there was, at particular points over the past two to three years, an imbalance between the number of investigators on the one hand and collection resources available to respond to the investigators’ intelligence requirements on the other. While the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service moved to better manage intelligence collection needs through the formation of the Collection Hub, this development took time to start working properly. Consequently, the imbalance between investigatory and collection resources led to considerable pressure on collection resources, particularly at the point that relatively large numbers of new investigators were brought into the investigation teams.

37

The New Zealand Intelligence Community’s report back on the Strategic Capability and Resourcing Review (which occurred after 15 March 2019) noted that recruitment and turnover challenges were continuing to impact the numbers of collection staff able to be deployed. It takes time for new staff recruits to be security vetted and cleared before they can be brought into the organisation and more time to train them to appropriate levels of skill and allow them to develop necessary levels of experience.81

Developing a Strategic Intelligence Analysis function

38

In 2015, the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service initiated a review of the security intelligence model used within the New Zealand Intelligence Community.82 The review primarily focused on the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service. It identified the need for a stronger strategic function to support its investigative efforts by proactively identifying and analysing future security threats. The Strategic Intelligence Analysis function was established in response, despite this not being funded under the Strategic Capability and Resourcing Review. At the time, the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service was the only Five Eyes intelligence agency without a dedicated strategic intelligence analysis capability.

39

The primary purpose of the Strategic Intelligence Analysis team is to provide the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service with strategic assessment of security intelligence issues (especially espionage and terrorism). The New Zealand Security Intelligence Service described its strategic intelligence function in the following terms:

…to provide [the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service] with practical understanding of security intelligence issues as they are occurring or emerging within New Zealand, in order to inform [the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service’s] decision-making. This capability enables [the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service] to look more broadly than just known threats and current investigative areas, by understanding the evolution of threats, and identifying emerging or future threat areas. This understanding is then used to guide [the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service’s] investigative and operational work, as well as resource allocation. For example, strategic analysis can be used to point part of our investigative effort towards new, emerging threats in addition to established areas of investigation.

40

A Capability Directorate was established in mid-2017,83 in part to build on the work undertaken in response to the 2014 Performance Improvement Framework review of the New Zealand Intelligence Community. Its role includes horizon scanning to understand the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service’s future capability needs.

41

Most of the Strategic Intelligence Analysis team’s work is tasked by investigative teams in the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service. It is occasionally tasked by other Public sector agencies. A few of its assessments are provided to the wider New Zealand Intelligence Community and other stakeholders. For example, its quarterly New Zealand Terrorism Updates were distributed to agencies represented on the Security and Intelligence Board, but it is unclear to what extent, if any, they guided the counter-terrorism efforts of those agencies.

42

In February 2019, an internal memorandum within the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service noted “enduring misconceptions of [the Strategic Intelligence Analysis team’s] role and purpose”. And the 2019 Arotake Review considered that the Strategic Intelligence Analysis team remained “a fledgling capability, whose role in guiding [the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service’s] intelligence functions does not yet appear to be fully embedded”.84

43

With its focus on guiding the operational activity of the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, the Strategic Intelligence Analysis team performed a different function to the Combined Threat Assessment Group (see Part 8, chapter 4). The Combined Threat Assessment Group’s assessments are intended to inform the approach to counter-terrorism at a whole-of-system level.

Staffing and turnover

44

The New Zealand Security Intelligence Service’s annual staff turnover target is eight percent. Annual staff turnover was 12.1 percent in 2018-2019, up from 10.3 percent in 2017-2018. Despite the New Zealand Intelligence Community putting in place a Diversity and Inclusion Strategy, retaining ethnically diverse staff has been a particular problem for the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service. Ethnically diverse staff represented 21.1 percent of turnover for 2018-2019. While the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service pointed out that its turnover rate is broadly consistent with the Public service as a whole, high turnover is problematic for an intelligence and security agency.

45

Capacity issues continue to be felt deeply in some areas. The 2019 Arotake Review singled out staffing levels in the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service’s Christchurch office as a problem and requiring consideration.85

5.6 How has the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service pursued its counter-terrorism efforts?

Operational priorities

46

The New Zealand Security Intelligence Service’s 10-Year Operational Strategy, released in June 2016, has been a key mechanism for it to apply the National Security and Intelligence Priorities (see Part 8, chapter 3). It sets out nine long-term strategic goals. The top three goals inform its prioritisation and resourcing decisions:86

Goal 1: mitigation of espionage and hostile foreign intelligence threats;

Goal 2: mitigation of serious domestic terrorism threats; and

Goal 3: establishment of an effective baseline picture of emerging terrorism threats.

47

Accordingly, counter-terrorism efforts, while high on the list of goals, sat behind efforts to counter espionage and hostile foreign intelligence. In practical terms, this meant that before 15 March 2019 approximately half of the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service’s investigative resources were dedicated to espionage and hostile foreign intelligence with slightly less being allocated to counter-terrorism.87 The higher priority placed on espionage and hostile foreign interference meant that more experienced investigators tended to be concentrated on those threats.88

48

New Zealand Security Intelligence Service staff told us about the complexity of managing competing priorities. This is particularly marked in relation to counter-espionage and counter-terrorism operations. The former tend to move at a slower pace than a counter-terrorism operation and often require a longer period of operational activity in order to bring results.

Evolving focus of effort

49

Up until 2018, the resources available to the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service’s counter-terrorism effort were devoted to what was seen as the presenting threat (as identified by lead information, intelligence collection, strategic assessments and international partner reporting) of Islamist extremist terrorism. These resources were almost fully engaged on the investigation of New Zealand supporters of Dā’ish seeking to participate in hostilities abroad to mount, or encourage or support terrorist attacks or undertake activities in support of terrorism in New Zealand.89

50

Before mid-2018 the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service was largely focused on monitoring known individuals where the nature of the threat was understood.90 Rebecca Kitteridge, Director-General of Security, told us that this was unsatisfactory, as it tied up resources that should be actively seeking out unknown threats.

51

The 2019 Arotake Review noted that the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service had long employed a “classical model” for its investigations, which is lead-based. This model is well suited to assessing known threats using established intelligence collection techniques but is less well suited to the development of a detailed picture of emerging threats in the security environment (see Part 8, chapter 10).91 The 2019 Arotake Review found that the classical model had served the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service well in relation to Islamist extremist threats. These threats largely (but not exclusively) dominated the New Zealand terrorism threatscape until early 2018.

52

In 2016 the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service’s 10-Year Operational Strategy identified establishing “an effective baseline picture of emerging terrorist threats” as a third goal. But this was deferred until there was sufficient capacity to carry out this work, which did not occur until May 2018. At that time, the Counter-Terrorism Unit instituted a new work programme, which required investigators to allocate 20 percent of their time to baselining and target discovery (see Part 8, chapter 10).

53

The baselining project looked at emerging threats motivated by a range of ideologies. This included a 12 month project focusing on right-wing extremist activity in New Zealand. In July 2018, the right-wing extremism project produced a report detailing information and intelligence requirements for collection units to pursue. The report also described the “Current Intelligence Picture”, which indicates that the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service had a limited understanding of the right-wing extremism environment in New Zealand at that time:

At present, little is known about the extreme right-wing environment in New Zealand.

…

The New Zealand Security Intelligence Service is currently unsighted to any individuals or groups who espouse an extreme right-wing ideology and promote the use of violence to achieve their objectives.

…

It is possible that a group or individual in New Zealand could associate with [extreme right-wing] groups or individuals offshore.

54

In response to the intelligence and information requirements, the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service’s online operations team began to look at right-wing forums.92 Additionally, the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service was engaging with a key partner, which had a well-established and active target discovery work programme, in order to further develop its capability in this area.93

55

The New Zealand Security Intelligence Service’s baselining project on right-wing extremism in New Zealand was not complete as at 15 March 2019. This meant it had a developing but still limited understanding of the threat of right-wing extremism as at 15 March 2019.

56

After 15 March 2019, the Counter-Terrorism Unit within the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service established a dedicated target discovery team. This team is in a “developmental stage” and has been scoping and re-scoping a number of discovery projects and engaging with other agencies who may be able to assist efforts. The Counter-Terrorism Unit’s Discovery Strategy was revised in August 2019. Since then, the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service’s organisational strategy has identified discovery as its first priority.

System awareness of unmitigated risk of right-wing terrorism

57

The deferral of the baselining of non-Islamist terrorism threats until the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service had sufficient additional capacity – that is until May 2018 – was consistent with the 2016 Strategic Capability and Resourcing Review Cabinet paper and the 2016 10-Year Operational Strategy. It was a considered decision by the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service.

58

The corollary of the recognition that there were threats that warranted baselining and the deferral of the baselining project was that there was a risk that was not being addressed. The existence of this risk was not explicitly highlighted with the Security and Intelligence Board and the Counter-Terrorism Coordination Committee. We will return to discuss this point in more detail in Part 8, chapter 15.

5.7 Concluding comments

59

In the years preceding 15 March 2019, the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service was rebuilding, from an extremely low base, its capacity to identify and respond to terrorism threats. Growing capacity and capability in an intelligence and security agency takes time and comes with particular challenges. So the rebuilding exercise was complex. It has, however, been implemented in a considered way and has resulted in an organisation that is far more capable than it was in 2016.

60

As the 2019 Arotake Review identified, the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service’s lead-based investigation model was not well suited to the development of a detailed picture of emerging threats. Such resources as were available to the counter-terrorism effort were, up until 2018, largely devoted to the presenting threat of Islamist extremist terrorism. This focus of effort was also contributed to by the very limited assessments from the National Assessments Bureau and the Combined Threat Assessment Group about threats of terrorism from other sources (see Part 8, chapter 4).

61

The deferral of the baselining project meant that, for the period between mid-2016 when the Strategic Capability and Resourcing Review money became available and mid-2018 when baselining began, the national security system was carrying a risk – the threat of non-Islamist extremism – the nature of which was not understood in any detail.

75. Intelligence and Security Act 2017, section 7.

76. Intelligence and Security Act 2017, section 9.

77. Intelligence and Security Act 2017, section 58.

78. Performance Improvement Framework, footnote 42 above.

79. United Kingdom Intelligence and Security Committee Report into the London Terrorist Attacks on 7 July 2005 (presented to Parliament May 2006) at page 38.

80. New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, footnote 57 above.

81. The significant lead in time required to bring a new recruit up to full performance was recognised by the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States in The 9/11 Commission Report. The Commission noted that it “takes five to seven years of training, language study, and experience to bring a recruit up to full performance”. See The 9/11 Commission Report: Final Report of the National Commission on Terrorist attacks upon the United States (2004) at page 90.

82. New Zealand Security Intelligence Service Review of the New Zealand Intelligence Community’s Security Intelligence Operating Model (Project Aguero) (2015).

83 .New Zealand Security Intelligence Service Performance Improvement Framework: Follow-up Self Review of the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service Te Pa Whakamarumaru (March 2018) at page 8.

84. New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, footnote 57 above at page 50.

85. New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, footnote 57 above at page 61.

86. New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, footnote 55 above.

87. New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, footnote 57 above at page 46. This contrasts with other comparable organisations – for example, 81 percent of MI5’s resources are used to support counter-terrorism work. See Security Intelligence Service, International Terrorism: the International Terrorism Threat to the UK (Undated) https://www.mi5.gov.uk/international-terrorism.

88. New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, footnote 57 above at page 57.

89. New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, footnote 57 above at page 46.

90. New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, footnote 57 above at page 51.

91. New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, footnote 57 above at page 10.

92. New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, footnote 57 above at page 96.

93. New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, footnote 57 above at page 91.