6.1 Overview

1

New Zealand Police are responsible for maintaining public safety and domestic law enforcement and have a core role in the counter-terrorism effort.

2

In this chapter we:

- explain the role of New Zealand Police in the counter-terrorism effort;

- describe reviews of counter-terrorism policing and international practice;

- assess New Zealand Police’s counter-terrorism activities;

- explain what New Zealand Police were doing about right-wing extremism;

- discuss what awareness the counter-terrorism system had of New Zealand Police’s capacity and capability gaps;

- describe the experiences of Muslim communities with New Zealand Police; and

- set out developments since 15 March 2019.

6.2 The role of New Zealand Police in the counter-terrorism effort

3

As explained in Part 2: Context, New Zealand Police are one of two counter-terrorism agencies. New Zealand Police seek to prevent crime and improve public safety, detect and bring offenders to account and maintain law and order. Their work also includes searching for missing persons, dealing with sudden deaths and identifying lost property. They have a visible presence in communities. This provides New Zealand Police with the ability to collect and analyse information about risks in and against communities. This is critical to the prevention of crime, including terrorist activity.94

4

New Zealand Police are active in Reduction, Readiness, Response and Recovery activities (see Part 2, chapter 4) within the counter-terrorism effort. For example, where an individual poses a risk, New Zealand Police may take direct action to prevent or disrupt an attack. This can occur through arrest and prosecution, issuing warnings or working with individuals to connect them with social support needed to divert them from violent extremism. Where the risk is imminent, New Zealand Police lead Response activities.

6.3 Reviews and international practice

5

Our review of the literature and international policing practice confirms that there is no single internationally-accepted standard for counter-terrorism policing. There are, however, a range of common components evident across similar countries (including Australia and the United Kingdom). These are consistent with key conclusions from reviews of New Zealand Police’s national intelligence and security systems and counter-terrorism efforts95 – that counter-terrorism policing requires a specialised, coordinated and integrated approach that includes prevention and community engagement. More specifically there are four critical components of counter-terrorism policing practice:

- Leadership, strategy and direction.

- A specialist counter-terrorism function.

- A whole-of-police effort.

- An intelligence function.

The assessment that follows is by reference to these four components.

6.4 Assessment of New Zealand Police’s counter-terrorism efforts

Leadership, strategy and direction

6

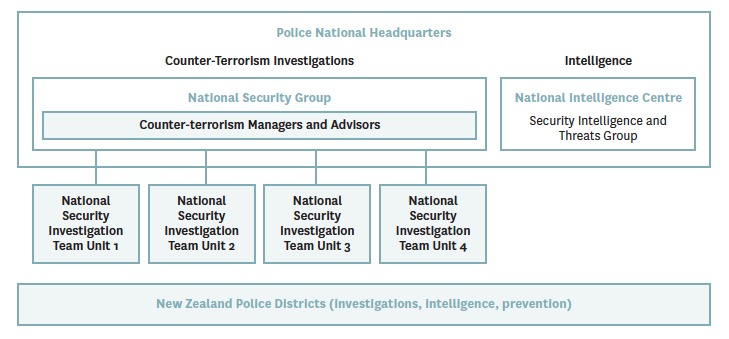

New Zealand Police’s current organisational structure for its counter-terrorism functions is outlined in the graphic below.

Figure 46: Counter-terrorism functions within New Zealand Police

7

A National Security Strategy, which set out New Zealand Police’s approach to national security (including counter-terrorism), expired in 2015 and has not been replaced. Those we spoke to within the New Zealand Police National Security Group were able to provide us with a clear and well-articulated explanation of their counter-terrorism approach. This was a New Zealand-specific model particularly focused on prevention and community policing. They attributed the lack of a current strategy document to delays in the finalisation of a whole-of-government counter-terrorism strategy with which New Zealand Police’s strategy would have to align. New Zealand Police had been strongly advocating for a whole-of-government counter-terrorism strategy and for changes to counter-terrorism legislation at the Security and Intelligence Board for a considerable period (see Part 8, chapters 3 and 13).

8

The absence of whole-of-government and New Zealand Police counter-terrorism strategies, and a lack of capacity hampered dissemination of the counter-terrorism policing model widely within New Zealand Police. The National Security Group at Police National Headquarters, which led this work, had only a few full-time equivalent staff.

Specialist counter-terrorism function

9

To operate effectively, New Zealand Police need to identify and investigate potential terrorist threats. This requires specialist teams, with investigative capability, and access to physical and technical surveillance, informant management and forensic accountancy capabilities.96

10

As at 15 March 2019, there was one National Security Investigations Team with four units spread across the country. These units were responsible for conducting and/or overseeing investigations related to national security threats. Their work included prevention, detection and disruption of terrorist threats.

11

Those in the National Security Investigations Team were described by New Zealand Police as experienced and capable investigators who had sufficient training in counter-terrorism investigations. Alongside investigation and prosecution, they also worked with individuals to identify what support they required to reduce their risk of engaging in violent extremism. They saw this as often more beneficial than waiting for arrest opportunities. This is consistent with international best practice, which prioritises early intervention by providing at-risk individuals with a range of support services to address their vulnerabilities.

12

International experience has also highlighted challenges with early intervention activities, as they target people who are seen as being at risk of engaging in criminal behaviour but who have not actually engaged in any criminal behaviour. The role of law enforcement agencies in early intervention therefore needs to be carefully managed to ensure that these activities are perceived by those involved as genuine efforts to safeguard and prevent harm, and not as an enforcement tool. New Zealand Police appeared to understand these challenges.

13

Through their early intervention work, New Zealand Police provided people at-risk with the structure and support needed to move them off the path towards violent extremism. They provided individually-designed case management plans or referred people to the Young Person’s Intervention Programme. This programme was a multiagency scheme designed to divert young people (aged 14–20) from violent extremism, which was supported by community groups. New Zealand Police involved in the programme felt that it was a useful early intervention tool, but that it was hampered by a lack of funding and limited involvement by community groups.

14

We were told that, before 15 March 2019, the National Security Investigations Team’s workload was “do-able”, but a “stretch”. The workload made it difficult at times to devote resources to early intervention and risk Reduction activity. Taking action when specific individuals were identified as a presenting threat took precedence. This was particularly noticeable in resource-intensive operational phases (such as surveillance), during which the National Security Investigations Team had to draw on resources from other parts of New Zealand Police. Pressure of work meant that the National Security Investigations Team did not have the capacity to develop a formal operating model and there was no leads case management system. While their way of operating offered flexibility, such as allowing a focus on early intervention, it also meant that processes, such as assessing risk, prioritising leads and investigations or closing cases, were inconsistent.

15

Recognising these capacity gaps, in 2016, New Zealand Police submitted a budget bid for increased counter-terrorism resource. This was the same budget round as the Strategic Capability and Resourcing Review funding was approved (see Part 8, chapter 2). New Zealand Police’s budget bid was unsuccessful. Additional resource was not approved until 2018, when funding for 18 new positions was provided to build counter-terrorism investigations capability and enhance the Police National Headquarters counter-terrorism function. There was comparatively little focus by the Security and Intelligence Board on discussing the resourcing of the overall counter-terrorism effort. This meant there was limited discussion of New Zealand Police’s counter-terrorism capacity. And, at a system level, the Public sector agencies involved in the counter-terrorism effort remained unaware of New Zealand Police’s resourcing gaps and their consequences.

16

Capacity issues were compounded by the lack of planning and preparation offences in the Terrorism Suppression Act 2002 (see Part 8, chapter 13). New Zealand Police devoted considerable resources to monitoring persons of concern. Some of these people were behaving in ways that may have resulted in prosecution for planning and preparation offences if such offences were provided for in the Terrorism Suppression Act.

A whole-of-police effort

17

Although counter-terrorism policing will often be driven by specialist units, these units need to be able to draw on the wider resources of the national organisation.97 New Zealand Police have national reach and connections into a wide range of communities through their everyday policing work. The interactions that frontline staff have with communities can provide crucial opportunities to identify emerging threats or people at risk of radicalisation and what support people need to divert from violent extremism. For this to be effective, police outside of specialist units need to have some understanding of indicators of, or behaviours that might lead to, violent extremism and of their roles and responsibilities in countering terrorism.

18

The National Security Group was charged with increasing counter-terrorism knowledge and capabilities throughout New Zealand Police so they would “know what to look for and how to engage with suspects”.98 The National Security Investigations Team made efforts to build knowledge throughout New Zealand Police, through an online training module on violent extremism distributed in 2018, discussions with District leadership on the threatscape and implications for New Zealand and specialist training for some District investigators. Some of these trainings and presentations included content on right-wing extremism, including a Senior Investigation Officer course run in Australia by the Australia New Zealand Counter-Terrorism Committee (see Part 8, chapter 17 for more detail on these presentations and training). But while these efforts were reportedly well received, the small number of staff in the National Security Group meant they struggled to fulfil the role of building knowledge throughout New Zealand Police in a comprehensive and systematic way.

19

As a result, the Districts were not well integrated into the counter-terrorism effort. Some staff in the Districts and other units described the National Security Investigations Team as operating in isolation, with limited scope for the Districts to contribute. In the absence of a national case management system for managing leads, there was no obvious place for District staff to record information of relevance regarding people of national security concern. Some District staff thought that this reduced opportunities for frontline staff to look out for relevant information and contribute to the counter-terrorism effort.

20

A 2015 review of New Zealand Police’s counter-terrorism capability recommended that a New Zealand Police national prevention coordinator be hired to ensure that counter-terrorism prevention activity would be embedded within District efforts.99 This coordinator was not in place before 15 March 2019. In the absence of a coordinator, there was limited, informal, coordination between the National Security Investigations Team and other prevention and community policing resources.

21

The National Security Investigations Team’s engagement with community policing resources and directly with communities was primarily focused on building relationships with Muslim communities. They did this, for example, through relationships with ethnic liaison officers (see Part 9, chapter 2) and direct engagement with masajid in some areas. The way the National Security Investigations Team went about this is in line with good practice. They were not, however, working in a planned and deliberate way with other parts of the community policing system to identify non-Islamist extremist threats, such as right-wing extremism.

Intelligence function

22

New Zealand Police’s intelligence model was developed in 2008. As designed, it consists of national-level and District-level functions, which are coordinated under one system. The National Intelligence Centre is responsible for collecting and assessing information to develop strategic intelligence that informs the Police Executive about emerging risks and where they should direct resources. Units within the National Intelligence Centre also deliver operational and tactical intelligence, such as the Security and Intelligence Threats Group, which is responsible for national security intelligence. Each of the 12 Districts has an intelligence team. They are responsible for collecting and assessing information to develop all tactical, most operational and some strategic level intelligence on District-level issues (for example, current or emerging crime trends) to inform local deployment priorities. Strategic intelligence products created at the national level should inform District-level intelligence collection and operational priorities.

23

As at 15 March 2019, New Zealand Police’s intelligence function was not working optimally. High staff turnover led to a loss of capacity and capability, variable use of intelligence across the Districts and a loss of strategic focus. In December 2018, New Zealand Police launched the Transforming Intelligence 2021 strategy in acknowledgement that the capacity and capability of their intelligence function had degraded. That strategy put in place a plan to renew the intelligence function.100

24

New Zealand Police’s intelligence function is central to the counter-terrorism policing effort, at both the tactical and strategic level. For counter-terrorism, tactical intelligence can involve gathering information to identify and build profiles of individuals or groups of concern, which are then used by investigators. Strategic intelligence is used to build a picture of current and emerging issues and therefore guides organisational priorities. Strategic intelligence is important in building a picture of the local counter-terrorism environment. The Financial Intelligence Unit also contributes intelligence to New Zealand Police’s counter-terrorism effort.

25

New Zealand Police’s strategic intelligence reporting could have provided a useful contribution to the national security system’s understanding of the domestic threatscape. Before 2015, New Zealand Police had been producing strategic intelligence reports on a wide range of domestic threats. We have discussed the most relevant of these in Part 8, chapter 4.

26

New Zealand Police’s strategic intelligence capability declined after 2014. There was limited strategic focus on counter-terrorism from the intelligence system. We heard that the wide remit of the Security and Intelligence Threats Group, combined with its limited capacity and competing demands, constrained what that group could realistically do on counter-terrorism. The National Intelligence Centre provided briefings to New Zealand Police leadership that included strategic level content on terrorism and violent extremism. However, the National Intelligence Centre did not produce many strategic products on counter-terrorism to inform national and District priorities. This, combined with the lack of capacity in District-level collections activity, meant that collection staff were not collecting information that would help to build a picture of the domestic extremist environment.

27

The New Zealand Police intelligence function also provides important tactical support to counter-terrorism efforts. The Security and Intelligence Threats Group runs daily scans across New Zealand Police information holdings for issues of national security concern and compiles assessments on individuals of concern. Their effectiveness relies on the quality of information being recorded in the databases. There were barriers to intelligence analysts accessing all of the information they needed, as New Zealand Police information is kept across multiple databases. Intelligence analysts in the National Intelligence Centre only recently gained access to the database that holds the National Security Investigations Team’s case profiles. Information being held in many places makes it harder to create a full intelligence picture.

28

The National Security Investigations Team’s North Island-based units each had their own embedded intelligence analyst. A decision to move the South Island national security intelligence analyst resources into the general pool of intelligence analysts was revisited after 15 March 2019. It was agreed that those resources could be based within the South Island unit if desired.

29

We heard that, before 15 March 2019, effort at the District level was directed to counter-terrorism (for example, scanning the local environment to generate leads) only where District leadership had an interest in it. District intelligence staff had not received specialist training on violent extremism indicators, meaning that their ability to undertake risk assessments and contribute to counter-terrorism efforts would have been limited.

6.5 What were New Zealand Police doing about right-wing extremism?

Intelligence assessments

30

In Part 8, chapter 4, we described how New Zealand Police produced intelligence reports on several right-wing extremist groups in New Zealand up until 2015. We observed that New Zealand Police had generally viewed right-wing extremism as more of a public order issue than a potential terrorist threat.

31

In 2014, New Zealand Police produced two intelligence assessments published by the National Assessments Committee of particular relevance to the extreme right-wing threat in New Zealand. These were the last formal assessments of extreme right-wing groups in New Zealand for national security purposes. This was before there was a global eruption of hateful content online in 2015 and 2016 (see Part 8, chapter 2). At this time the nature of right-wing extremism was changing. International developments demonstrated that traditional street-based organisations were being supplemented by new groupings and that the indicators of allegiance to new right-wing extremist groups were different to those of the past.

32

From 2015 until 15 March 2019, New Zealand Police were not producing strategic intelligence on far right individuals and groups. They were aware of new far right groupings, but they had not assessed the groups systematically or produced a national intelligence assessment of the contemporary far right environment. We have also seen some evidence that New Zealand Police had given some thought to the possibility that Muslim communities in New Zealand could be the target of threats, such as the 2018 National Security Situation Update identifying periods in which Muslim individuals and communities were potentially at heightened risk of attack, such as Ramadan.

33

New Zealand Police undertook preliminary steps to produce a national assessment of the right-wing extremism environment subsequent to a meeting with the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service in late 2018 but limited progress had been made by 15 March 2019. As a result, New Zealand Police were not in a position to update their understanding of the indicators of right-wing extremism and disseminate this information to the front line.

Leads on right-wing extremists

34

The National Security Investigations Team receives leads through a variety of channels, including from their own activities and from public reporting, frontline reporting and other agencies (for example, the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service). They described themselves as “threat agnostic” – meaning that when they receive a lead, they use the same assessment criteria regardless of the ideological source of the threat. In assessing the risk of an individual or group they look for indicators of an intention to use violence in support of an extremist ideology and the capability (the skills, knowledge and resources) to do so. There are a range of indicators that can be used to assess a person’s radicalisation and mobilisation to violence, such as having accessed extremist websites, made statements inciting the use of violence, purchased weapons or conducted online research into targets.

35

The majority of the National Security Investigations Team’s resources were devoted to Islamist extremism. The reason they provided for this focus of effort was that the majority of the leads they received were related to possible Islamist extremism. There were aspects of the ways New Zealand Police generated leads – for example, the nature of their engagement with Muslim communities – that were conducive to generating Islamist extremist leads. New Zealand Police were successful in mitigating the threats they identified. For example, between August 2015 and January 2018, New Zealand Police arrested 17 individuals of national security interest for a variety of offences and issued 40–50 warnings for extremism-related objectionable publication offences.

36

We were also provided examples from the National Security Investigations Team of leads related to right-wing extremism that met the risk threshold and were pursued.

37

The National Security Investigations Team acknowledged to us that they did not consistently use standardised criteria for assessing leads. Staff made decisions about whether to continue assessing an individual based on professional judgement. It is expected that individuals would use their knowledge and experience to inform their decision-making. However, neither the assessment criteria nor individuals’ professional judgement were informed by detailed updated indicators of right-wing extremism after 2015-2016. Inconsistent use of assessment criteria can create risks that decisions are influenced by unconscious bias. This risk would have been greater given that New Zealand Police had limited knowledge and understanding of recent strands of right-wing extremism and therefore less experience assessing individuals associated with these ideologies.

38

We saw examples of frontline or other staff (such as ethnic, Pacific or iwi liaison officers) alerting the National Security Investigations Team to possible cases of right-wing extremism. However, to be assured that New Zealand Police were treating all reports of potential right-wing extremism seriously we would need to see that all staff could recognise indicators of right-wing extremism. We did not receive assurances that there was sufficient awareness and training on right-wing extremism for this to be the case.

6.6 System awareness of New Zealand Police capacity and capability gaps

39

The gaps in New Zealand Police’s counter-terrorism efforts – the limited capacity of their investigations team, the degraded nature of their intelligence function and the fact that they were no longer producing assessments on the extreme right-wing and strategic assessments on domestic extremism – were not explicitly highlighted with the Security and Intelligence Board and Counter-Terrorism Coordination Committee.

6.7 Experiences of Muslim communities with New Zealand Police

40

Counter-terrorism policing relies on people having trust and confidence in police so that they are comfortable reporting threats against themselves and their communities and threats within their communities.

41

We heard from ethnic liaison officers about their efforts to build meaningful and mutually-beneficial relationships with Muslim communities (see Part 9, chapter 2). However, being part of the counter-terrorism effort presents challenges for the parts of New Zealand Police tasked specifically with community policing, such as ethnic, Pacific and iwi liaison officers. For police staff focused on community engagement, being involved in counter-terrorism activities can risk compromising community trust because they can be seen by communities as using the relationships they build primarily for collecting intelligence.

42

International experience has shown that to manage these tensions, police need to work in partnership with communities. A partnership approach does not exclude the collection of community intelligence. But it requires that any intelligence collection occurs alongside police prioritising the security concerns that community members bring to them and working collaboratively to increase their safety and security.

43

The National Security Investigations Team was aware of the importance of not stigmatising and alienating communities. For example, when concerns were raised by Muslim communities about people charged for offences under the Films, Videos, and Publications Classification Act 1993, the National Security Investigations Team attended public forums and developed a brochure explaining that the reason for the charges was that downloading objectionable material was a national security indicator. They explained that they used a graduated approach where they would only charge people after they had first warned the individual. Their intention was early disengagement with charging as a last resort. However, we heard that the National Security Investigations Team did not always act in ways that were cognisant of the ethnic, Pacific or iwi liaison officers’ need to maintain community trust.

44

We heard a range of concerns from Muslim individuals and communities about reports they have made to New Zealand Police about suspicious or threatening behaviour (see Part 3: What communities told us). In some instances they felt that staff did not have the ability to recognise behaviours, signals or patterns of incidents that could signify possible hate crimes or signs of extreme right-wing activity. We were told of instances where people did not see staff writing anything down when making reports. We heard that people rarely received any follow up from New Zealand Police after making reports. This meant that many of the Muslim individuals and communities we heard from felt that New Zealand Police did not take their concerns seriously.

45

At the same time, efforts to engage with Muslim communities have been viewed by some as primarily intended to gather intelligence about possible Islamist extremists. We have observed that Muslim individuals and communities have often been proactive and cooperative with New Zealand Police efforts to identify and mitigate the risk of Islamist extremism. However, for many, the perceived overt focus on Islamist extremism without a corresponding focus on threats they were reporting created frustration and diminished their trust in New Zealand Police.

46

A summary of New Zealand Police’s interactions with members of Muslim communities since 2010 demonstrates that New Zealand Police looked into many reports of suspicious or threatening behaviour made by Muslim individuals or communities. In some cases, New Zealand Police spoke to those accused, issued warnings and pursued prosecution. In other cases, New Zealand Police staff felt unable to act due to a lack of evidence or legislative constraints regarding hate crime (see Part 9, chapter 4). Where New Zealand Police had acted, it is not always clear that they reported back to the complainants about the outcomes of their inquiries. We heard from community members that where New Zealand Police had reported back, this was not always in a way that reassured the complainant that the issue had been thoroughly investigated.

6.8 Developments since 15 March 2019

47

Since 15 March 2019, New Zealand Police have been developing a more formalised and integrated approach to counter-terrorism. They are now developing an operational model that proposes a more graduated response, where low-risk cases are managed by frontline staff and high-risk cases stay under the management of the National Security Investigations Team. There is a focus on building District capabilities across investigations, intelligence and prevention, and building connections between the National Security Investigations Team and Districts. New Zealand Police have now implemented the recommendation made in 2015 for a dedicated role focused on coordinating prevention work. A national prevention coordinator (see above) now leads the newly created Multi-Agency Coordination and Intervention Programme, which builds on the Young Person’s Intervention Programme but is for adults.

48

Widespread changes to intelligence capability and capacity are occurring through Transforming Intelligence 2021. Changes are also being made to improve intelligence support for counter-terrorism, which is now identified as a priority area for New Zealand Police intelligence.

49

Immediately after 15 March 2019, there was an influx in public reporting of possible national security leads, including leads relating to right-wing extremism (see Part 8, chapter 3). A National Security Case Management process is being developed to formalise and standardise the leads prioritisation process and manage the increase in public reporting. A standardised risk assessment tool will be developed and the model will allow the Security and Intelligence Threats Group, National Security Investigations Team and District intelligence to manage leads through a centralised location and process. New Zealand Police also created a list of individuals of right-wing extremist concern. This list was developed by reviewing existing New Zealand Police holdings and from new information reported by the public.

6.9 Concluding comments

50

The absence of both a whole of government counter-terrorism strategy (see Part 8, chapter 3) and a New Zealand Police counter-terrorism policing strategy limited the ability of staff outside specialist units to understand the contribution they could make to preventing and countering terrorism. While the specialist units within New Zealand Police showed evidence of good practice, especially in their focus on early intervention and prevention, their efforts were hampered by their limited capacity. This also limited their ability to build counter-terrorism policing capability throughout New Zealand Police and as a result many frontline police staff lacked a clear understanding of how to recognise indicators of violent extremism. Overall, New Zealand Police lacked adequate specialist counter-terrorism capacity and were not using their full policing resource in their efforts to counter violent extremism and terrorism.

51

Before 2015, New Zealand Police had been paying some attention to right-wing extremism in New Zealand by identifying and monitoring the general criminal activities of traditional street-based groupings and by managing their potential threat to public order. The risk of right-wing extremism was assessed in the two 2014 assessments we have referred to and in passing in the 2018 National Security Situation Update. They also opened and pursued leads with possible connections to the extreme right-wing. But in the years preceding 15 March 2019 the focus of New Zealand Police’s counter-terrorism effort was undoubtedly on Islamist extremism.

52

By 2015, New Zealand Police’s intelligence function had degraded, limiting what it could contribute to understanding the domestic terrorism environment. Without an up-to-date understanding of right-wing extremism in New Zealand, including the emerging groups and networks, New Zealand Police were not well placed to understand the threat and how to identify it.

53

As noted above, since the 15 March 2019 terrorist attack, New Zealand Police have created a list of individuals of right-wing extremist concern. That this list was developed (in part) by New Zealand Police reviewing their existing holdings demonstrates that they had information on the extreme right-wing already. New Zealand Police were also able to gather much more intelligence on the extreme right-wing after 15 March 2019, as more people had become aware of the potential risks to look out for due to heightened public awareness.

54

The limited capacity of New Zealand Police’s national security investigations team and the degraded nature of their intelligence function were not brought to the attention of the Security and Intelligence Board and Counter-Terrorism Coordination Committee. For this reason the residual risk the counter-terrorism effort was carrying was therefore not fully understood.

55

New Zealand Police understood the importance of community trust and confidence for their counter-terrorism activities to be successful and had made efforts in this area. However, for many Muslim individuals, the focus on their communities as potential sources of terrorist activity and perceived corresponding lack of attention paid to threats against them diminished their trust in New Zealand Police. It was evident that New Zealand Police had been acting on concerns raised by Muslim individuals and communities but this was not always properly communicated. This highlights the important role feedback loops play in providing trust and the need for more focus from New Zealand Police on providing this reassurance.

75. Intelligence and Security Act 2017, section 7.

76. Intelligence and Security Act 2017, section 9.

77. Intelligence and Security Act 2017, section 58.

78. Performance Improvement Framework, footnore 42 above.

79. United Kingdom Intelligence and Security Committee Report into the London Terrorist Attacks on 7 July 2005 (presented to Parliament May 2006) at page 38.

80. New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, footnote 58 above.

81. The significant lead in time required to bring a new recruit up to full performance was recognised by the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States in The 9/11 Commission Report. The Commission noted that it "takes five to seven years of training, language study, and experience to bring a recruit up to full performance". See The 9/11 Commission Report: Final report of the National Commission on Terrorist attacks upon the United Staets (2004) at page 90.

82. New Zealand Security Intelligence Service Review of the New Zealand Inelligence Community's Security Intelligence Operating Model (Project Aguero) (2015).

83. New Zealand Security Intelligence Service Performance Improvement Framework: Follow-up Self Review of the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service Te Pa Whakamarumaru (March 2018) at page 8.

84. New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, footnote 57 above at page 50.

85. New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, footnote 55 above at page 61.

86. New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, footnote 55 above.

87. New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, footnote 57 above at page 46. this contrasts with other comparable organisations - for example, 81 percent of MI5's resources are used to support counter-terrorism work. See Security Intelligence Service, International Terrorism: the international Terrorism Threat to the UK (Undated) https://www.mi5.gov.uk/international-terrorism.

88. New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, footnote 57 above at page 57.

89. New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, footnote 57 above at page 46.

90. New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, footnote 57 above at page 51.

91. New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, footnote 57 above at page 10.

92. New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, footnote 57 above at page 96.

93. New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, footnote 57 above at page 91.94. R Lambert and T Parsons “Community-Based Counter-Terrorism Policing: Recommendations for Practitioners” (2017) 40 Studies in Conflict and Terrorism.

95. New Zealand Police National Security Capability Assessment (March 2011); New Zealand Police National Security and Counter-Terrorism Capability Review (September 2015).

96. KM Dunn, R Atie, M Kennedy, JA Ali, J O’Reilly and L Rogerson “Can you use community policing for counter-terrorism? Evidence from NSW, Australia” (2016) 17 Police Practice and Research at page 196.

97. Sharon Pickering, Jude McCulloch and David Wright-Neville Counter-Terrorism Policing: Community, Cohesion and Security (Springer, New York, 2008).

98. New Zealand Police (2015), footnote 95 above.

99. New Zealand Police (2015), footnote 95 above.

100. The Transforming Intelligence 2021 programme includes 11 streams of work: Intelligence Operating Model, National Security, Target Development Centre, Open Source, Child Protection Offender Register, Critical Command Information, Collections, Intelligence Systems, Performance, Training and Intelligence Support to major events.