4.1 Introduction

1

As we will explain, Public sector agencies were not aware of the individual’s intent to carry out the 15 March 2019 attack. One of the major issues we must address in our report is why this was so. To do this we must review how Public sector agencies detect potential terrorists and the activities and preparation of the individual. As part of this exercise, we examine New Zealand’s counter-terrorism effort (see Part 8: Assessing the counter-terrorism effort). This provides context for our consideration of whether the individual’s activities and preparation could or should have been detected by Public sector agencies (see Part 6: What Public sector agencies knew about the terrorist).

2

This chapter provides a description of New Zealand’s broader national security system and overviews of the intelligence function and the counter-terrorism effort, both of which are part of the national security system.

4.2 National security system

An all hazards, all risks approach

3

One of the most important duties of government is protecting the security of the nation. In our report we discuss national security, which is defined in New Zealand’s National Security System Handbook as “the condition which permits the citizens of a state to go about their daily business confidently free from fear and able to make the most of opportunities to advance their way of life”.50

4

The broad definition of national security reflects an “all hazards, all risks” approach to national security. This has been the policy approach of the New Zealand government since 2001. All significant risks to national security – whether from inside or outside New Zealand, from human or non-human sources – are addressed by the national security system. These include threats such as espionage, transnational organised crime, terrorism, cyber-security attacks, natural disasters and pandemics.

Threat versus risk

5

In our report we use the terms “threat” and “risk.” They are not the same thing. A threat is a source of potential damage or danger. Risk is determined by assessing the likelihood of a threat occurring and the seriousness of the consequences if it does. The more likely the threat occurrence, and the more severe the likely consequences, the greater the risk. In the case of terrorism in New Zealand, the threat of terrorism was assessed as being low before 15 March 2019, but the consequences of a terrorist attack were considered sufficiently serious that the risk was assessed as high.

The 4Rs approach

6

New Zealand’s approach to national security is based on four areas of activity referred to as “the 4Rs”:

- Reduction – identifying and mitigating risks.

- Readiness – developing national security capabilities before they are needed.

- Response – taking action in the face of an imminent/close threat or in response to one.

- Recovery – coordinated efforts to recover from an event.

7

So the system has two orientations - a proactive mode (Reduction and Readiness for an event that has not occurred) and a reactive mode (Response and Recovery from an event that has occurred).

8

We are interested mainly in the proactive mode of the national security system – Reduction and Readiness – and in relation to the threat and risk of terrorism. The proactive mode focuses on risk management and building national resilience. This includes building resilience of New Zealand’s infrastructure, institutions and communities. Due to views expressed by Muslim communities, we have also looked at certain aspects of the Recovery phase. Our Terms of Reference specifically excluded us from looking into the Response to the terrorist attack.

Roles within the national security system

9

The scope of the all hazards, all risks and 4Rs approach means that many Public sector agencies have roles in the national security system. For each type of national security risk, there is intended to be a lead agency. Other agencies make contributions based on their agreed roles and responsibilities.

10

Local government, the private sector and local communities also have increasingly important roles within the national security system. As we describe in Part 8, chapter 3, however, the efforts of Public sector agencies to engage the wider public in national security have been limited.

11

Some 30 Public sector agencies have roles in national security. This creates a need for governance of the system as a whole, including central coordination.

12

The national security system operates at three levels:

- The prime minister and ministers.

- Chief executives.

- Officials (within Public sector agencies with national security responsibilities).

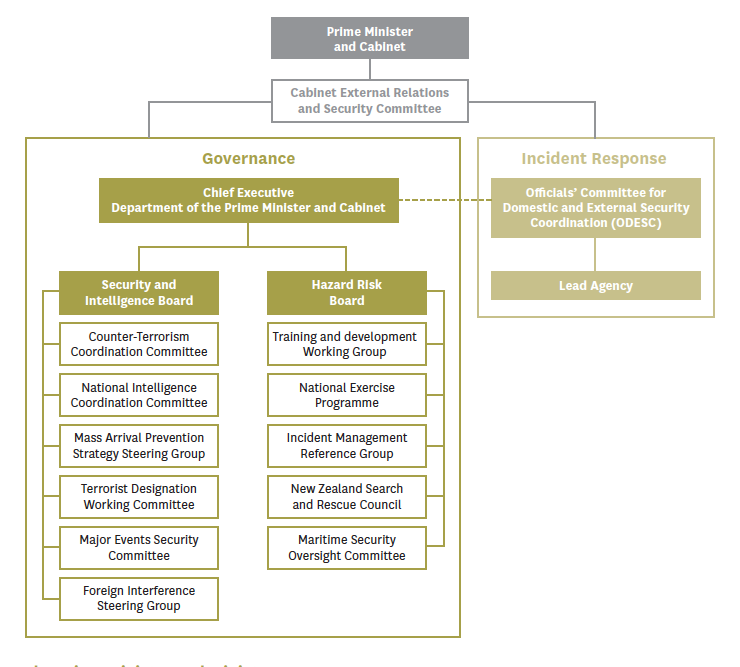

Figure 3: Governance of the National Security System

The prime minister and ministers

13

New Zealand’s national security is a core responsibility of the prime minister and executive government. The prime minister is the Minister for National Security and Intelligence, and the Cabinet is at the top of the national security system. It considers decisions and recommendations from the Cabinet External Relations and Security Committee. Membership of this committee includes the prime minister and ministers responsible for key agencies involved in national security.51 Cabinet approves the National Security and Intelligence Priorities, which we discuss later in this chapter.

Chief executives

14

Like ministers, chief executives of Public sector agencies have collective and individual responsibilities. They are responsible to the appropriate minister for their department’s “responsiveness on matters relating to the collective interests of government”.52 They also have more specific responsibilities, such as providing free and frank advice to ministers. Sometimes chief executives have responsibilities established by legislation specific to their agency. For example, the police commissioner must act independently of ministers regarding the maintenance of order, the enforcement of the law and the investigation and prosecution of offences.53

15

Two governance boards bring together the chief executives of agencies with national security responsibilities:

- The Security and Intelligence Board focuses on external and internal security threats and intelligence issues.

- The Hazard Risk Board deals with emergency management and civil defence matters and hazard risks.

16

Both boards are chaired by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Between them they cover all hazards, all risks.

17

It is the Security and Intelligence Board that is relevant for our purposes. It includes the chief executives (or their delegates) of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, the Government Communications Security Bureau, the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, the Ministry of Defence, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, New Zealand Customs Service, New Zealand Defence Force, New Zealand Police and the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service. Other chief executives may be invited to attend meetings if required.

18

The Security and Intelligence Board reports to the Cabinet External Relations and Security Committee. The Board’s purpose, as defined in its terms of reference, is to:

- lead, build and govern the security intelligence system;

- hold the system to account for delivery;

- build system capabilities and capacity; and

- remain alert to current threats and opportunities.

19

The Security and Intelligence Board meets monthly. Counter-terrorism is a regular feature of its discussions.

Officials

20

Several subcommittees of the Security and Intelligence Board bring together officials from different agencies to focus on particular national security issues. The subcommittees most relevant to our inquiry are the Counter-Terrorism Coordination Committee and the National Intelligence Coordination Committee (see Part 8, chapter 3).

The role of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet

21

The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet is the lead Public sector agency on national security. It is responsible for coordinating the activity of the agencies involved in the national security system. It does this through its National Security Group. This group also advises the prime minister and other ministers on national security matters.

22

As will become apparent, the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s coordination role leaves a large measure of autonomy for the chief executives of the Public sector agencies involved in the national security system. This is particularly true of the Government Communications Security Bureau, New Zealand Police and the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service. We discuss the leadership and coordination role of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet in some detail in Part 8, chapter 3.

The challenges facing the national security system

23

New Zealand’s national security system requires contributions from many different agencies. This presents some challenges.

24

First, these agencies are often responsible for many different work programmes (including programmes unrelated to national security). The agencies in the national security system therefore require mechanisms to prioritise their resources and their work programmes. Other countries – the United Kingdom for example – have national security strategies to help with this. As we discuss in Part 8, chapter 3, New Zealand did not have national security or counter-terrorism strategies in place before 15 March 2019 despite numerous attempts since at least 2012 to produce them.

25

Second, the national security system is affected by similar structural issues that impede interagency collaboration in other systems or networks of agencies in the Public sector. As Te Kawa Mataaho Public Service Commission recently said, “our public management system is fragmented and struggles to act cohesively to address cross-cutting problems”.54 This is because within the current framework, the individual responsibility of chief executives to individual ministers incentivises officials to focus on their own agency’s outputs and outcomes. There is less incentive for them to focus effort across agencies and, ultimately, the individual gains of each agency will almost always take priority over interagency efforts.55 There are more incentives for Public sector agencies to work vertically than horizontally. This hinders effective collaboration to address complex issues that cut across agency boundaries. The role of the central agencies (the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Te Kawa Mataaho Public Service Commission and the Treasury) is to provide leadership on cross-cutting issues. The Public Service Act 2020 provides new models aimed at making interagency collaboration easier to achieve.

26

Third, there are uncertainties and difficulties with the concept of resilience in New Zealand’s approach to national security. Resilience is arguably to achieve for infrastructure and institutions – for example, through physical changes to a building or measures to protect New Zealand’s information systems against cyber threats. Resilience for people is not so straightforward. A one-size-fits-all approach to resilience is unlikely to be effective when it comes to building community resilience. What is instead required is an appropriate separation between the concept of physical resilience and psychological resilience. This separation should guide the necessarily different approaches to building resilience of things and in people.56

27

There is evidence to suggest that community participation in national security plays an important role in community resilience. For this to happen, there must be deep engagement of the national security system with the communities, civil society, local government and the private sector.57

4.3 The intelligence function

28

Intelligence is a key contributor to almost all activities in New Zealand’s counter-terrorism effort, which we discuss later in this chapter. It can indicate the emergence of a harmful ideology or inform decisions to designate a terrorist organisation or disrupt an imminent terrorist attack.

What is intelligence?

29

Intelligence is usually regarded as information that has been collected, processed and used to inform decision-making.58 Ideally, it consists of the “right information, understood in context, delivered to the right customers, at the right time”. Sometimes intelligence comes from information that is publicly available, or is “open-source” – for example, the internet, newspapers, journals and other non-secret sources. Such intelligence is increasingly exploited by intelligence agencies around the world.

30

In contrast, secret intelligence is based on information obtained covertly, often using classified techniques and tools. Secret intelligence can be collected covertly from the internet or through more traditional means, such as human sources. Sometimes it is a combination of the two.

What guides intelligence activities?

31

Intelligence resources are scarce. As our report will illustrate, Public sector agencies must make tough choices about where to focus their resources. At a high level, the National Security and Intelligence Priorities set the focus area for all intelligence activity across the national security system. In the case of the Government Communications Security Bureau and the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, the Priorities authorise and limit their intelligence activity. That is, their intelligence collection and analysis must contribute to the National Security and Intelligence Priorities.59

32

The National Security and Intelligence Priorities were updated approximately every three years before 15 March 2019. The current National Security and Intelligence Priorities were adopted in December 2018 and an unclassified version was published in an appendix to the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s 2019 Annual Report. In September 2020, the National Security and Intelligence Priorities were published on the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet's website.60 Terrorism is one of the 16 National Security and Intelligence Priorities. The wording of the Priority is broad, and therefore covers a wide range of intelligence activity, directed at a number of threats and risks. Choices about which threats to allocate resources to rests with each agency. We discuss in more detail in Part 8, chapter 3 how the National Security and Intelligence Priorities operate in practice and particularly in respect of terrorism.

The New Zealand Intelligence Community

33

The Government Communications Security Bureau, the National Security Group of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (including the National Assessments Bureau), and the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service (including the Combined Threat Assessment Group) make up the New Zealand Intelligence Community.

34

The New Zealand Security Intelligence Service focuses on a range of threats, including terrorism. It has a significant role in the counter-terrorism effort. Its collection methods are largely based on human intelligence activities. Human intelligence is information collected from people. It may come from a range of sources – from confidential human sources to tip-offs from members of the public. Other collection methods are also used, including physical surveillance, tracking devices, technical interception and listening devices – most of which require a warrant under the Intelligence and Security Act 2017.

35

The Government Communications Security Bureau is New Zealand’s signals intelligence agency. It mainly gathers intelligence through the collection and analysis of electronic communications such as telephone calls, text messages and online communication. The capabilities used by the Government Communications Security Bureau are specialised and highly technical. Most of the work it carries out also requires a warrant under the Intelligence and Security Act.

36

Some parts of the New Zealand Intelligence Community assess rather than collect intelligence. In New Zealand, intelligence assessments are mainly provided by two entities – the National Assessments Bureau and the Combined Threat Assessment Group. These agencies fuse multiple pieces of intelligence from various sources (for example, intelligence from other Public sector agencies and international partners) and produce assessments to inform decision-making. They do not provide policy advice or recommend actions as a result of their assessments.61 This is done by the policy or operational agency, relevant to the particular issue.

37

The National Assessments Bureau prepares intelligence assessments on matters of national security, international relations and economic wellbeing.62 Its assessments are either commissioned by customers (other Public sector agencies such as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade) or self-initiated.

38

The Combined Threat Assessment Group sits within New Zealand Security Intelligence Service and may include secondees from other agencies, including the Department of Corrections, the Government Communications Security Bureau, the New Zealand Defence Force and New Zealand Police. It provides independent assessments to inform the national security system of the threat posed by terrorism to New Zealand and New Zealand’s interests (including those offshore). Its assessments usually have an immediate-to-12 month focus (except in relation to planning for a major event in New Zealand, such as a Rugby World Cup).

39

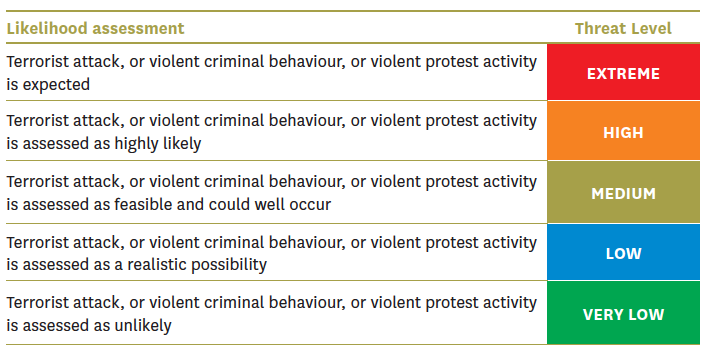

One of the Combined Threat Assessment Group’s roles is to set and regularly review New Zealand’s terrorism threat level. This is fixed on a six-level scale from “negligible” to “extreme” and is under continual evaluation. Threat assessments differ from the national counter-terrorism risk profile, which also considers the consequences of threat occurrence and determines the assessed risk.

Figure 4: Scale of terrorism threat level

Other Public sector agencies that collect and assess intelligence

40

A number of other Public sector agencies collect and assess intelligence. In Part 8: Assessing the counter-terrorism effort we also discuss the intelligence functions of Immigration New Zealand, New Zealand Customs Service and New Zealand Police.

Partner agencies

41

The Government Communications Security Bureau and the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service actively cooperate with international partner agencies in collecting and sharing intelligence information, most particularly with partners in the other Five Eyes countries - Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States of America. New Zealand Public sector agencies also work with non-Five Eyes countries and groupings.

42

The New Zealand Security Intelligence Service and Government Communications Security Bureau depend heavily on their international partner agencies. This was well explained in the 2016 Cullen-Reddy Report and remains valid:

As national security threats are becoming more complex and transnational, it would be extremely expensive for New Zealand to create a wholly self-reliant intelligence community. This is particularly so given our small size when compared to some of our partners. Through foreign intelligence partnerships, New Zealand draws on a much greater pool of information, skills and technology than would otherwise be available to it. For example, a foreign partner may have greater access to intelligence that requires the right mix of ethnic, cultural and language backgrounds to collect and analyse. Intelligence partnerships also help New Zealand prioritise and focus intelligence collection and assessment resources on the areas most important to us, while avoiding intelligence gaps.

We obtained some statistics from the Agencies that give a sense of how significant our international partnerships are. Of all security leads the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service investigates, around half are received from foreign partners. These represent possible threats to the security of New Zealand, most of which we would not be able to discover on our own (for instance, because they have a foreign source). New Zealand also gains considerably more from its international partnerships than we provide in return. For every intelligence report the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service provides to a foreign partner, it receives 170 international reports. Similarly, for every report the Government Communications Security Bureau makes available to its partners, it receives access to 99 in return.63

43

International partner agencies also assist in other ways, with training, secondment of staff and cooperation on operational best practice.

Monitoring and oversight of the intelligence community

44

Given the intrusive powers that can be used by intelligence and security agencies (such as surveillance), oversight is necessary to help ensure that the agencies’ powers are used lawfully and appropriately, with minimal impact on members of the public. We discuss this oversight in detail in Part 8, chapter 3.

4.4 New Zealand’s counter-terrorism effort

Terminology

45

We use the term “the counter-terrorism effort” to refer to all activities undertaken by Public sector agencies (including the counter-terrorism agencies, the New Zealand Intelligence Community and the border agencies) to prevent, mitigate, respond to and disrupt actual or potential terrorist threats. This may involve disrupting the travel of potential or actual terrorists, or their financing or other logistical support.

46

Over the past decade, the ways that countries have undertaken counter-terrorism has evolved. This evolution is based on the understanding that the traditional approach can and should be complemented with activities that target the social, political and economic drivers of violent extremism and terrorism. This has resulted in a much wider range of actors, including local authorities, social policy agencies, non-governmental organisations and community groups becoming involved in counter-terrorism. This more comprehensive approach is often referred to as “countering violent extremism”. We have found the experiences in other jurisdictions are instructive for New Zealand’s efforts.

47

There are different usages of the term countering violent extremism, but we use it to describe efforts to intervene before a person is radicalised to undertake a terrorist attack. Such efforts can cover a spectrum of activities. At one end are targeted interventions designed to support individuals showing signs of radicalisation. At the other end are activities that aim to prevent the emergence of violent extremism though building social cohesion. This includes a wide range of interventions focused on improving social outcomes, such as youth development, education and employment. While it is accepted that the efforts to build social cohesion support the aims of counter-terrorism, it is also generally accepted that these efforts should be pursued separately to counter-terrorism. Social cohesion has broader aims and is worthwhile in itself. We discuss this in more detail in Part 8: Assessing the counter-terrorism effort and Part 9: Social cohesion and embracing diversity.

The key Public sector agencies

48

An effective counter-terrorism effort requires that multiple Public sector agencies work together as an integrated whole.

49

The agencies of primary interest for our purpose are set out below:

- The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet coordinates the counter-terrorism effort and provides strategic guidance and policy advice.

- The Government Communications Security Bureau provides specialist intelligence support to New Zealand Police's and the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service's terrorism investigations. It also receives a large amount of signals intelligence from Five Eyes partners about foreign extremist individuals and organisations. This information is provided to relevant Public sector agencies when appropriate.

- New Zealand Police are the lead agency for Response to a terrorism event that is underway or an imminent or close threat. They also collect intelligence on and investigate potential terrorist threats and have roles in the prevention of violent extremism.

- The New Zealand Security Intelligence Service collects intelligence on and investigates possible and actual terrorist threats. It does not have enforcement functions – meaning, for example, it cannot arrest and prosecute a person. That is a role for New Zealand Police. The New Zealand Security Intelligence Service uses the intelligence it collects to inform (when appropriate) the New Zealand government and other Public sector agencies such as New Zealand Police, as well as international partner agencies, to enable mitigation of terrorism risks.

50

The agencies with the primary roles in the counter-terrorism effort are New Zealand Police and the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service. We refer to them as the “counter-terrorism agencies”.

51

Also of some relevance are mechanisms that are in place for the identification of potential terrorists before they board aircraft bound for New Zealand and at the border. These primarily involve Immigration New Zealand, New Zealand Customs Service and the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service. We discuss this later in our report in Part 8: Assessing the counter-terrorism effort.

Where do terrorism leads come from?

52

Detection of potential terrorists usually starts with a lead suggesting that a particular person or perhaps a group of people pose a threat of terrorism. This may be based on information supplied by a Public sector agency or international partner agency. It may also result from a tip-off from a member of the public or the private sector. The more security aware New Zealand communities are, the greater the likelihood of tip-offs.

53

In some countries, there are public-facing counter-terrorism strategies that inform the public of threats and risks, explain the government’s efforts to manage them and promote an appropriate role for the public. An example is a “see something, say something” message, with advice on what sorts of things might warrant a member of the public’s attention and action. Before 15 March 2019, there was no such strategy in New Zealand.

54

New Zealand Police and the NewZealand Security Intelligence Service are not merely passive recipients of leads. For instance, an existing investigation into a subject of interest may result in the identification of another person who warrants investigation. Other efforts to generate leads include monitoring (by various mechanisms) of certain places (including on the internet) and the activities and communications of certain groups of people.

55

Analysing data sets for indicators of terrorism (such as travel patterns, financial transactions and social media activity) may provide opportunities to detect suspicious activity. Lead generation of this kind is based on identifying behaviours that can serve as indicators of terrorist intent or preparation. We discuss this in more detail in Part 8: Assessing the counter-terrorism effort.

50. Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet National Security System Handbook (August 2016) at page 7.

51. See Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet website (ERS) Cabinet External Relations and Security Committee https://dpmc.govt.nz/publications/co-19-4-cabinet-committees-terms-reference-and-membership.

52. Public Service Act 2020, section 52(1)(b).

53. Policing Act 2008, section 16(2).

54. Te Kawa Mataaho Public Service Commission Impact Statement: State Sector Reform (2019) at page 3 https://www.publicservice.govt.nz/assets/Legacy/resources/Impact-Statement-State-Sector-Act-Reform.pdf. This issue has been highlighted in successive reviews over the past 30 years including: New Zealand Government Review of State Sector Reforms (1991); Te Kawa Mataaho Public Service Commission Ministerial Advisory Group on the Review of the Centre (2001); Te Kawa Mataaho Public Service Commission Better Public Services Advisory Group Report (2011).

55. This “commitment problem” is solved in the private sector through the use of contracts. However, Public sector agencies cannot enter into enforceable contracts with one another because they are not distinct legal entities. They are, rather, separate administrative units of the same legal entity, the Crown.

56. Christopher Rothery New Zealand’s National Security Framework: A recommendation for the development of a National Security Strategy (a thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations and Security Studies at The University of Waikato, 2018).

57. Christopher Rothery, footnote 56 above.

58. “Raw” intelligence is unprocessed information that has been collected by an intelligence and security agency but which, by force of time constraints or other circumstance, may sometimes have to be taken into account in decision-making.

59. Section 10(1) of the Intelligence and Security Act 2017 requires their collection and analysis of intelligence to be consistent with the priorities identified by the government, which, in practice, means the National Security and Intelligence Priorities.

60. Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet website National Security and Intelligence Priorities https://dpmc.govt.nz/our-programmes/national-security-and-intelligence/national-security-and-intelligence-priorities.

61. This helps to ensure that assessments are impartial and that assessments are not tailored to support a particular decision.

62. Intelligence and Security Act 2017, section 243.

63. Hon Sir Michael Cullen KNZM and Dame Patsy Reddy DNZM Intelligence and Security in a Free Society: Report of the First Independent Review of Intelligence and Security in New Zealand (Cullen-Reddy Report) (2016) at page 45.