3.1 Overview

1

As at 15 March 2019, the Arms Act 1983 provided for three categories of licences and a range of endorsements authorising the licence holder to possess pistols, restricted weapons or military style semi-automatic firearms. With the exception of pistols, there was no limit on the number of firearms or amount of ammunition that a firearms licence holder may purchase.

Figure 15: New Zealand firearms licence and endorsement types

| Licences | |

A |

Standard firearms licence – allows a person to have and use, without supervision, any type of firearm (except pistols, military style semi-automatic firearms and restricted weapons). |

D |

Dealer’s firearms licence – allows a person to sell and make firearms and airguns. Valid for one year and can only be used for one place of business. |

V |

Visitor’s firearms licence – allows a person visiting New Zealand for less than 12 months to use firearms for hunting or competitions in New Zealand and to apply to have endorsements to use controlled firearms. |

| Endorsements | |

B |

B Endorsement – to possess up to 12 pistols and use for target shooting and to be an active member of an approved pistol club recognised by the Commissioner of New Zealand Police. |

C |

C Endorsement – either:

|

E |

E Endorsement – to possess military style semi-automatic firearms. |

F |

F Endorsement – to own pistols and restricted weapons for hire or sale, including as an employee of a dealer. Usually issued alongside an E Endorsement to enable dealing in military style semi-automatics as well. |

2

The individual was granted a firearms licence without endorsements on 16 November 2017. Throughout the report we will refer to his licence as a standard firearms licence. This is sometimes called an “A Category” licence.

3

The standard firearms licence did not authorise the individual to possess pistols, restricted weapons or military style semi-automatic firearms – the types of firearms for which endorsements are required. Firearms that can lawfully be possessed by the holder of a standard firearms licence are sometimes referred to as “A Category firearms”.

4

The purpose of this chapter is to describe the process, not evaluate it. An evaluation of the firearms licensing system, which includes the firearms licensing process, is provided in chapter 4 of this Part.

5

In this chapter we outline the firearms licensing process for a standard firearms licence, with a primary focus on the application of the fit and proper person test. We will address:

- the legislative context;

- New Zealand Police policy and operational guidance;

- the people who administer the process;

- an overview of the process; and

- determining whether an applicant is a fit and proper person.

At the end of the chapter we identify the steps in the process that are significant to our inquiry.

3.2 The legislative context

6

In this chapter, we discuss the legislative context as it was before 15 March 2019. At the time, the firearms licensing process was based on sections 23 and 24 of the Arms Act and regulations 14–16 of the Arms Regulations 1992.

7

Sections 23 and 24 of the Arms Act provided:

23 Application for firearms licence

(1) Any person who is of or over the age of 16 years may apply at an Arms Office to a member of the Police for a firearms licence.

(2) Every application under subsection (1) shall be made on a form provided by a member of the Police.

(3) A person who is the holder of a firearms licence may, before the expiration of that firearms licence, apply for a new firearms licence.

24 Issue of firearms licence

(1) Subject to subsection (2), a firearms licence shall be issued if the member of the Police to whom the application is made is satisfied that the applicant—

(a) is of or over the age of 16 years; and

(b) is a fit and proper person to be in possession of a firearm or airgun.

(2) A firearms licence shall not be issued to a person if, in the opinion of a commissioned officer of Police, access to any firearm or airgun in the possession of that person is reasonably likely to be obtained by any person—

- whose application for a firearms licence or for a permit under section 7 of the Arms Act 1958, or for a certificate of registration under section 9 of the Arms Act 1958 has been refused on the ground that he is not a fit and proper person to be in possession of a firearm or airgun; or

- whose certificate of registration as the owner of a firearm has been revoked under section 10 of the Arms Act 1958 on the ground that he is not a fit and proper person to be in possession of a firearm; or

- whose firearms licence has been revoked on the ground that he is not a fit and proper person to be in possession of a firearm or airgun; or

- who, in the opinion of a commissioned officer of Police, is not a fit and proper person to be in possession of a firearm or airgun.

8

As at September 2017, when the individual initiated the licensing process, regulations 14, 15 and 16 of the Arms Regulations provided:

14 Applicants to undergo theoretical test

Every applicant for a firearms licence shall, unless a commissioned officer of Police otherwise directs,—

- undergo a course of training which is conducted by a member of the Police or a person approved for the purpose by a member of the Police and which is designed to teach the applicant to handle firearms safely; and

- pass such theoretical tests as may be required to determine the applicant’s ability to handle firearms safely (being tests conducted by a member of the Police or a person approved for the purpose by a member of the Police).

15 Supply of particulars for firearms licence

(1) Every application for a firearms licence shall be in writing, and shall be signed by the applicant.

(2) The application shall state—

- the full name of the applicant; and

- the date of birth of the applicant; and

- the place of birth of the applicant; and

- the address and occupation of the applicant; and

- the place at which the applicant carries on his or her occupation; and

- the name and address of a near relative of the applicant; and

- the name and address of a person (not being a near relative of the applicant) of whom inquiries can be made about whether the applicant is a fit and proper person to be in possession of a firearm; and

- whether the applicant has been convicted of any offence, whether in New Zealand or any other country; and

- whether the applicant has previously made application to be issued with a firearms licence whether in New Zealand or any other country and has been refused.

16 Place of application

(1) An applicant for a firearms licence shall attend in person at an Arms Office and shall complete at that Arms Office his or her application for a firearms licence.

(2) The Arms Office at which the applicant attends shall be either—

- the Arms Office nearest to the applicant’s place of employment; or

- the Arms Office nearest to the applicant’s place of residence.

9

Minor amendments were made to these regulations in January 2019. These provided that the regulation 14(b) tests could be practical, as well as theoretical, and cleared the way for applications to be made electronically.

3.3 New Zealand Police policy and operational guidance

10

The Arms Manual is the primary New Zealand Police policy document on the administration of the Arms Act. Sitting under it are the Master Vetting Guide, which provides training notes for firearms licensing staff, and the Firearms Licence Vetting Guide, an operational document that sets out questions that Vetting Officers should ask applicants and referees during interviews. It also provides the forms on which Vetting Officers record the answers given by applicants and referees.

3.4 The people who administer the process

11

Sections 23(2) and 24(1) of the Arms Act use the phrase “member of Police”. This is not restricted to those who are sworn police officers, but extends to all New Zealand Police employees. The licensing process is usually administered by non-sworn Police employees. This was the case for the individual’s application.

12

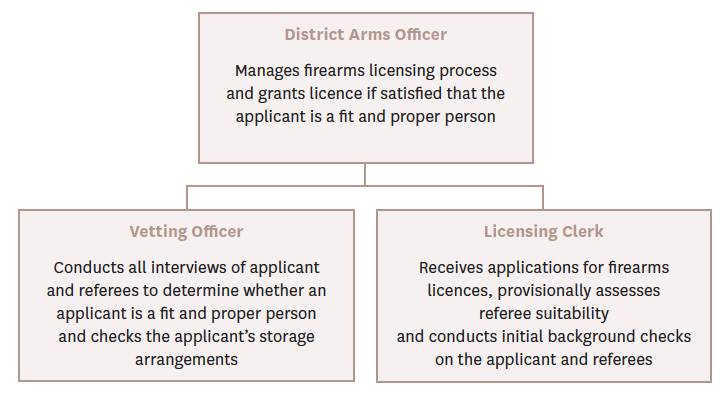

We outline below the roles of those involved in the decision to grant a firearms licence.

Figure 16: Roles of those involved in the firearms licensing process

13

Under section 24 of the Arms Act, a licence can be approved by a non-sworn Police employee, such as a District Arms Officer, but can only be refused by a sworn police officer, with the rank of inspector or higher. In the event of a licence application being refused, there is a right of appeal to the District Court.

3.5 An overview of the process

14

The steps towards obtaining a licence are as follows:

Figure 17: How New Zealand Police process a firearms licence application

1. Applicant completes and submits a paper application form

The applicant signs a declaration on the form to confirm that the information provided is correct. The completed application with proof of payment of fee is presented to New Zealand Police. The applicant must also attend, and pass, a Firearms Safety Course developed by New Zealand Police and run by New Zealand Mountain Safety Council instructors.

2. Licensing Clerk provisionally assesses application

The Licensing Clerk provisionally assesses the suitability of nominated referees and conducts initial background checks. The Licensing Clerk searches New Zealand Police’s National Intelligence Application database for any relevant information about the applicant and referees.

3. District Arms Officer assesses application for disqualifying factors

The District Arms Officer receives the file and reviews the application and, if it is appropriate for further processing, liaises with Vetting Officers.

4. Vetting Officer interviews referees

The Vetting Officer interviews the referees following the process set out in the Firearms Licence Vetting Guide.

5. Vetting Officer interviews applicant at home and conducts storage check

The Vetting Officer interviews the applicant following the process set out in the Firearms Licence Vetting Guide. Interviews take place in the applicant’s home and the Vetting Officer checks for appropriate firearms storage.

6. District Arms Officer reviews application for approval or refusal

The District Arms Officer reviews the application and referee interviews and then approves the firearms licence application or refers it to a police officer with the rank of inspector or above with a recommendation that it be declined.

3.6 The significance of the fit and proper person test

15

Under the Arms Act prior to 15 March 2019, a standard firearms licence lasted for 10 years and permitted the holder to possess any firearm other than a pistol, a restricted weapon, or a military style semi-automatic firearm. There was no firearms registry, meaning that there was no record of the number and type of firearms owned by the holder of a standard firearms licence.

16

All of this meant that the application of the fit and proper person test was fundamental to the effective operation of the Arms Act. Despite some legislative changes since 15 March 2019, this remains the case.

3.7 Who is a fit and proper person?

17

The phrase fit and proper person is not defined in the Arms Act and, prior to amendments made after 15 March 2019, little legislative guidance was provided as to how the fit and proper person test should be applied.

18

On the basis of earlier court decisions, factors a decision-maker might have taken into account prior to 15 March 2019 included:

- the applicant’s general character and temperament;9

- whether the applicant is a risk to themselves or others with firearms;10

- gang membership (although this will not automatically rule out an applicant);11 and

- previous convictions (although these will not automatically rule out an applicant).12

19

The Arms Manual defines a fit and proper person as a person of good character, who can be trusted to use firearms responsibly and will abide by the laws of New Zealand. It sets out a list of reasons why someone might not satisfy the test.13 These include having:

- been the subject of a protection order;

- shown no regard for the Arms Act or the Arms Regulations;

- been involved in substance abuse;

- committed a series of minor offences, or a serious offence, against the Arms Act, or a serious offence against any other Act;

- committed crimes involving violence or drugs;

- affiliations with a gang involved in committing violent offences or in conflict with another gang;

- past or present involvement in relationship disputes involving violence or threats of violence; and

- exhibited signs of mental illness or attempted to commit suicide or cause other injury to themselves.

Not included are extreme political opinions, racism or any other beliefs.

3.8 Information available to New Zealand Police from the National Intelligence Application and other sources

20

Information about an applicant or referee can be accessed through the National Intelligence Application – an information database used by New Zealand Police to manage information relevant to operational policing. The database includes:

- driver’s licence details;

- driver demerit and suspension history;

- youth aid involvement;

- family violence incidents;

- notification alerts (for example, mental health, violence, gang associations, vehicles, locations, organisations);

- history reports (such as charges against the person and bail conditions); and

- convictions

It also includes details about those who hold firearms licences, which may be relevant in relation to referee checks.

21

New Zealand Police may also conduct further checks, such as criminal history checks through the International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL). A medical certificate from the applicant’s general practitioner to certify the applicant’s mental stability may also be requested.

22

Overseas criminal history checks are limited and are not carried out routinely. Under its rules, the International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL) will only check an applicant’s overseas criminal convictions if that person is suspected of having committed an offence. New Zealand Police do not routinely ask applicants who have lived overseas to supply criminal history checks from other jurisdictions. This means identification of prior convictions relies on self-disclosure.

23

Similar considerations apply to medical certificates, as they are only sought if the applicant or referee discloses a medical condition that might have an impact on the applicant’s mental or physical suitability to possess a firearm or they behaved at the interview in such a way as to suggest such a condition.

3.9 Nomination and acceptance of referees

24

Regulations and guidance on the nomination of referees are complex. In order to deal with this complexity, we set out the law and policy in substantial detail.

25

Regulation 15(2)(f) of the Arms Regulations requires the applicant to provide “the name and address of a near relative of the applicant”. Regulation 15(2)(g) requires the nomination of a person who is not a near relative of the applicant “of whom inquiries can be made about whether the applicant is a fit and proper person”. We refer to both persons as the “referees”.

26

Neither the Arms Act nor the Arms Regulations require the referees to be interviewed. The Master Vetting Guide stipulates that, for every application, the near-relative referee must be interviewed face-to-face and the other referee must be interviewed face-to-face, only in the case of first-time applicants.

27

The Master Vetting Guide refers to the near-relative referee in this way:

This is the person who lives with, and probably best knows, the applicant in a personal sense. Be prepared to interview any previous spouse/partner.

28

Some applicants are unable to provide a near-relative referee who lives with them and can be interviewed in person. This is addressed by the Master Vetting Guide which, when dealing with the near-relative referee, provides:

If the applicant does not have a spouse/partner/next of kin, or the next of kin does not live with the applicant, interview the person who lives with them, or a person who is likely to know them best in a personal sense.

29

The Master Vetting Guide thus provides for the substitution of the near-relative referee. In this respect, there is an apparent inconsistency with the Arms Manual and the Firearms Licence Vetting Guide which indicate that a near-relative referee is a requirement.

30

Common sense requires all documents to be read together. This is consistent with the Arms Manual which provides that the Firearms Licence Vetting Guide and the Master Vetting Guide direct the vetting of applications. The front cover of the Firearms Licence Vetting Guide advises that “[b]efore conducting the vetting please ensure that you understand the Master Vetting Guide”. The District Arms Officer and the Licensing Clerk are responsible for the initial assessment of whether a near-relative referee can be dispensed with and replaced with an unrelated referee. When doing so, they are expected to act consistently with the Master Vetting Guide.

31

What all of this means is that an applicant who nominates a near relative who is living overseas or unable to be interviewed in person is usually advised to nominate another referee “who is likely to know them best in a personal sense” and is living in New Zealand.

3.10 Initial background checks of the applicant and referees

32

Upon receipt of the application, the Licensing Clerk carries out basic National Intelligence Application checks as to the applicant’s suitability to hold a firearms licence and the appropriateness of the two referees. The Licensing Clerk creates a paper file that includes printouts of the checks and forwards it to the District Arms Officer. If the checks show that the applicant is not a fit and proper person, the application is put to a police officer with the rank of inspector or higher for refusal. If nothing of note arises from these checks, the relevant parts of the file are sent to Vetting Officers.

33

Vetting Officers do not receive the National Intelligence Application printouts. Instead, if information arises from such checks that might be relevant to vetting, this is noted by the District Arms Officer in the paper file for discussion by Vetting Officers with applicants and/or referees.

3.11 The interview process

34

Vetting Officers are responsible for interviewing both the applicant and the referees as part of the application process.

35

Vetting Officers receive the relevant parts of the firearms licence application file and arrange in-person interviews with the applicant and the two referees at their respective homes.

36

The Firearms Licence Vetting Guide states that referees should be interviewed separately and before the applicant is interviewed. The applicant must not be present during these interviews. Conducting the interviews in this order allows the Vetting Officer to build a better understanding of the applicant and, in particular, to explore with referees any points of interest that can later be discussed with the applicant. This order of interviews is not always followed as it depends on the availability of those being interviewed and other practical considerations.

37

If the applicant and referees live in the same District, the same Vetting Officer will usually interview all of them, although this may not be possible due to staff availability. Where they do not all live in the same District, different Vetting Officers will be involved.

3.12 Referee interviews

38

The Firearms Licence Vetting Guide requires the Vetting Officer to ask for the referee’s personal details. If the referee holds a firearms licence the licence number is recorded.

39

Questions to determine the nature of the relationship between the applicant and referee are included in the preliminary section. For the near-relative referee, the questions are:

- What is your relationship to the applicant?

- How long have you known the applicant?

- Do you live with the applicant? And, if so, How long?

- How would you describe this relationship?

In the case of the other referee, the questions are:

- How long have you known the applicant?

- What is your relationship to [the] applicant?

40

The Firearms Licence Vetting Guide is written on the premise that there is a near-relative referee. Beyond the general questions that we have set out, it does not provide a template for testing the depth of the relationship between the applicant and referee. In particular, there is no guidance for Vetting Officers as to how they should assess whether the referee knows the applicant sufficiently well to comment on whether they are a fit and proper person, even though that is the primary purpose of inquiring into the nature of the relationship.

41

The Firearms Licence Vetting Guide provides questions that focus on the applicant’s attitude towards firearms and any traits of the applicant (or anyone in the applicant’s household) that may be relevant to the safe use of firearms. If any issues are identified, such as substance misuse, mental health issues or previous convictions, further details are required.

42

Finally, the referee is asked to comment on why they consider the applicant to be suitable to have firearms, if they would have concerns for the safety of any person if the applicant had access to firearms and any reason why New Zealand Police might not issue a firearms licence to the applicant. Vetting Officers are to look out for indications of a referee being afraid of, or coerced by, the applicant.

43

There is space at the end of the referee section for the Vetting Officer to provide comments and to summarise the interview, including observations of the referee’s behaviour, demeanour and their home.

44

Each referee initials the bottom of the pages of the Firearms Licence Vetting Guide where their answers have been recorded. Referees also fill in their names, the date and sign the Firearms Licence Vetting Guide declaring that the answers they gave are true and correct.

3.13 Applicant interview

45

A Vetting Officer interviews the applicant in person at their home and checks the security of storage arrangements to ensure that they meet the requirements of regulation 19 of the Arms Regulations.

46

The applicant must show the Vetting Officer proof of having passed the Firearms Safety Course.

47

The applicant’s interview is directed by the questions set out in the Firearms Licence Vetting Guide.

48

The first section is aimed at establishing why the applicant is applying for a firearms licence. The applicant must provide the Vetting Officer with their reasons for wanting a firearms licence and where they intend to use firearms, their experience with firearms and firearms interests (such as target shooting), whether they are a member of a firearms club or association and the precautions to be taken if firearms are lent to others.

49

The personal history section of the interview addresses whether the applicant has been referred to a psychiatrist or psychologist, has come to police attention (including for drink driving or traffic convictions) or has ever been refused a firearms licence (in New Zealand or elsewhere). Any information that has arisen from the background checks (including any overseas inquiries) that is of concern will be put to the applicant for comment.

50

There is a section in the Firearms Licence Vetting Guide addressing alcohol and drug use, including medication, and whether the applicant has attempted suicide or if they have had any adverse events in their life in the last 12 months.

51

The applicant is asked the same questions as their referees regarding the details of people who have access to the household and if those people display any traits that may make them unsafe to have access to firearms.

52

The last section attempts to identify the applicant’s attitudes towards firearms with questions similar to those asked of referees, including whether the applicant considers that they are suitable to have firearms and if they would have any concerns for the safety of any person if they had a firearm.

53

The Vetting Officer will then make a recommendation as to whether the applicant should be issued a firearms licence based on the interviews and inspection. The Vetting Officer provides a short statement outlining the reasons for the conclusion reached.

54

If the referees have been interviewed before the applicant, this information is available to the Vetting Officer when the recommendation is made. If a different Vetting Officer interviewed the referees, the Vetting Officer making the recommendation may talk to that Officer to get a better understanding of the referees and their comments on the applicant’s suitability to possess a firearm.

55

The applicant’s complete file is then returned to the District Arms Officer in the District where the application was made.

3.14 The decision of the District Arms Officer

56

The District Arms Officer reviews the report of the Vetting Officer (or their reports if there was more than one) and will grant the licence if satisfied the applicant is a fit and proper person to possess firearms. If the District Arms Officer is not satisfied the applicant is a fit and proper person, the application is referred to a police officer of the rank of inspector or higher for decision under section 24(2) of the Arms Act.

3.15 Steps in the process that are of significance to our inquiry

57

As we will explain, the individual initially put forward his sister Lauren Tarrant, who lived in Australia, as his near-relative referee and gaming friend (see Part 4, chapter 2), who lived in New Zealand, as his other referee. Lauren Tarrant was not acceptable as a referee because she could not be interviewed in person and she was not contacted. The individual’s gaming friend was substituted for her and gaming friend’s parent became the other referee.

58

The steps in the process as it was applied to the individual that are of concern to us involve the substitution of gaming friend as the near-relative referee, the acceptance of gaming friend’s parent as the other referee, the fact that Lauren Tarrant was not contacted and the referee interviews.

59

We discuss these issues in chapter 5 when we review in detail the process that was applied and in chapter 6 where we evaluate the adequacy of that process.

9. Police v Cottle [1986] 1 NZLR 268 (HC).

10. Jenner v Police [2016] NZDC 4102.

11. See Innes v Police [2016] NZDC 4538. However, compare Fewtrell v Police [1997] 1 NZLR 444 (HC); and Mallasch v Police [2009] DCR 596 (DC).

12. Bush v Police [1991] DCR 385 (DC); Flynn v Police DC Christchurch CIV-2010-009-605, 7 October 2010; Fewtrell v Police, footnote 11 above; Mallasch v Police, footnote 11 above; and Jenner v Police, footnote 10 above.

13. New Zealand Police Arms Manual (Wellington, 2002) at paragraph 2.29(2).